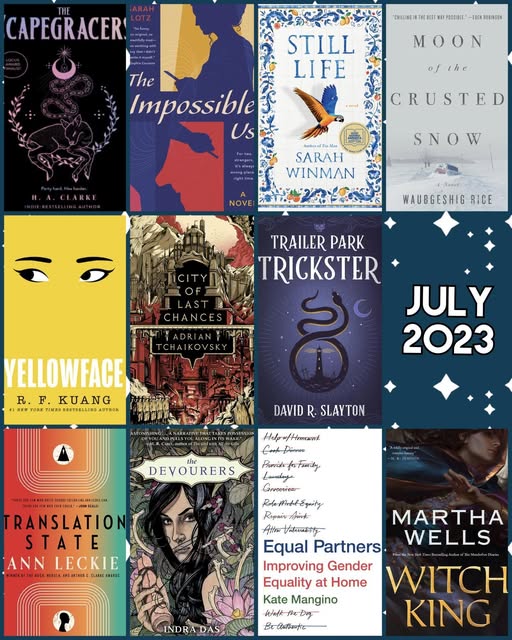

July was a relatively light reading month because family visited and we went on vacation! (Funny enough, I get less reading done on vacation than when I’m at home. Mark of a good vacation.)

The Scapegracers, by H.A. Clarke: The narrator of the Scapegracers, a teenage lesbian witch named Sideways Pike, has never been cool; however, when a trinity of confident, popular girls hires her to perform a showy spell for their Halloween party, she finds in them both a coven for her magic and an unexpected gift of friendship. The other girls are the opposite of insecure: they are brimming with righteousness and rage, ready to rain down curses on anyone who mistreats them or makes them feel lesser (mostly self-centered teenage boys). There are some threats from scary witchfinders and some weird gatekeeping from the occult establishment going on in the background, but mostly this book is a ferocious celebration of loyalty and magic. I love the defiant rejection of the “mean girls clique” trope, and also the diverse cast. First in a series.

The Impossible Us, by Sarah Lotz: Epistolary alternate-universe romp. After struggling author Nick and sassy dressmaker Bee make accidental contact through a misdirected email, they continue to correspond, finding in each other kindred spirits. They eventually make plans to meet… which is when they figure out that they actually live in different universes. Their respective actions after this discovery really do take this book into a new level. Even though things get super weird, the chemistry between Nick and Bee, and their snappy email conversations, keep the book going. Enjoyable plot and shenanigans, though if you start thinking too hard about the ramifications there are some iffy consent issues.

Still Life, by Sarah Winman: A slow, patient journey following Ulysses Temper through four decades (with occasional interludes with Evelyn Skinner, art historian). In 1944 Florence, British soldier Ulysses makes unexpected connections with the people that follow him back to his home in London, and eventually draw him back to Italy. Though Ulysses is the main character, the excellent ensemble cast around him, and their connections to one another, provide the warm heart that centers the story. I love how each of them is allowed space to grow, learn, and change, and how they each do their best to support one another. The writing is just gorgeous and both London and Florence are beautifully and wistfully rendered.

Moon of the Crusted Snow, by Waubgeshig Rice: Post-apocalyptic (though you don’t know it at the beginning) thriller, documenting the experience of a small Anishinaabe community in a reservation in northern Ontario. As the community is already pretty isolated, even more so as winter approaches, their awareness that civilization is collapsing comes slowly; first the power is cut off, then their fuel shipment never arrives. As the tribe attempts to maintain order and community safety, intruders escaping the crumbling south arrive and throw things into disarray. The narrator, a quiet, solid hunter named Evan Whitesky, quietly maintains family and community ties even as he begins to suspect the new arrivals of more sinister intentions. Well-paced, smoothly written.

Yellowface, by R.F. Kuang: When star author Athena Liu dies suddenly, June Hayward pockets her latest manuscript, about Chinese laborers, and then rewrites it and releases it under the name “Juniper Song” (her first and middle names). When the book becomes a smash success, June is accused of misleading people into thinking she might have Chinese ancestry, and finds herself haunted by Athena’s ghost wherever she turns. The book raises questions about racism in the publishing industry, diversity as performance, and ownership in art, but immerses it all in June’s inescapable trainwreck of an unreliable first-person narrative. There is barely a single likeable character in this book but it moves along incredibly well.

City of Last Chances, by Adrian Tchaikovsky: Ilmar is a city at the edge of the Palleseen empire, and one conquered in name but perhaps not in spirit; it is full of restless natives, bitter refugees, starry-eyed students, and ruthless criminals, and also sits on the edge of a haunted magical forest, last resort for the desperate. Tchaikovsky assembles a cast of archetypes and then proceeds to make them into whole characters that grate on one another’s edges and force one another into growth, and sets it against a background of cultural repression and inevitable rebellion. Fascinating read.

Trailer Park Trickster, by David R. Slayton: Book #2 featuring Adam Binder, the queer warlock from a trailer park who just can’t stop saving people (even those who might not deserve saving). This one has him returning to his roots and investigating the increasingly creepy foundations of his family life; meanwhile, his love interest Vicente finds himself navigating dangerous elven politics. I liked the book in general but didn’t like the ongoing trope of “lovers are too busy with mortal peril to discuss their relationship, therefore the angst will continue” which looks like it’ll continue into the third book. Sit down and talk to one another, gentlemen, it’s healthier in the long run.

Translation State, by Ann Leckie: Set in Leckie’s Radch universe, this starts out as a missing-persons mystery and ends with an impassioned argument over one’s right to determine one’s own destiny. I love how Leckie uses truly inventive alien biologies and philosophies to investigate very human questions of identity, self-determination, and found family. Slow start, tense finish, great read.

The Devourers, by Indra Das: South Asian speculative fiction, though it also touches on Nordic and other shapeshifter myths. Narrator Alok Mukherjee is a history professor who meets a mysterious figure who claims to be a half-werewolf; fascinated, Alok agrees to record the stranger’s stories, some oral and some written on human skin. As the stranger’s tale unfolds and Alok is drawn further into the fantastically violent and turbulent history, the relationship between the two of them deepens as well. I liked how the story wove together the mythologies of different cultures, and I also enjoyed how Das took time to develop Alok’s character instead of having him be a passive listener to a story far more interesting than his own life.

Equal Partners, by Kate Mangino: Full disclosure: I’ve met Kate Mangino, and found her book to be every bit as thoughtful, forthright, and considerate as she is. The subtitle for this book is “Improving Gender Equality at Home,” and addresses the imbalance in household gender roles created by harmful social norms. The book doesn’t just lay out examples and statistics, but gently points out familiar social behaviors that can actually perpetuate the problem. Each chapter also offers guided discussion topics and thought exercises to help readers become aware of their own stances and provide avenues for improvement, if it is desired. The book is carefully written to address as wide a spectrum of the modern family as possible, regardless of gender, sexual orientation, generation, and family structure. Even though I consider myself fairly educated and aware of these issues, I still found myself taking many notes on how to be a more equal parent and a more equality-focused person in conversation. Gender norms are deep-seated and addressing them is difficult, but this book provides an informative and understanding base from which to make a start.

Witch King, by Martha Wells: The best thing about Martha Wells’ narrators is that their general exasperation with everything makes them immediately relatable, no matter how weird their selves and circumstances… which is good, because the reader is otherwise thrown straight into a fantasy culture and magic system with absolutely no explanations. This book’s viewpoint character, Kai, is a demon who possesses the bodies of dying humans, and whose closest friends are powerful witches and warriors — useful because they seem to have some very terrifying enemies as well. Through adventure and flashback, Wells builds a portrait of how Kai and his friends were brought together, and how they became instrumental in the formation of the empire’s current political balance. Most of the plot threads are tied together neatly at the end, but it also feels like Wells might be doing some worldbuilding in preparation for future adventures.