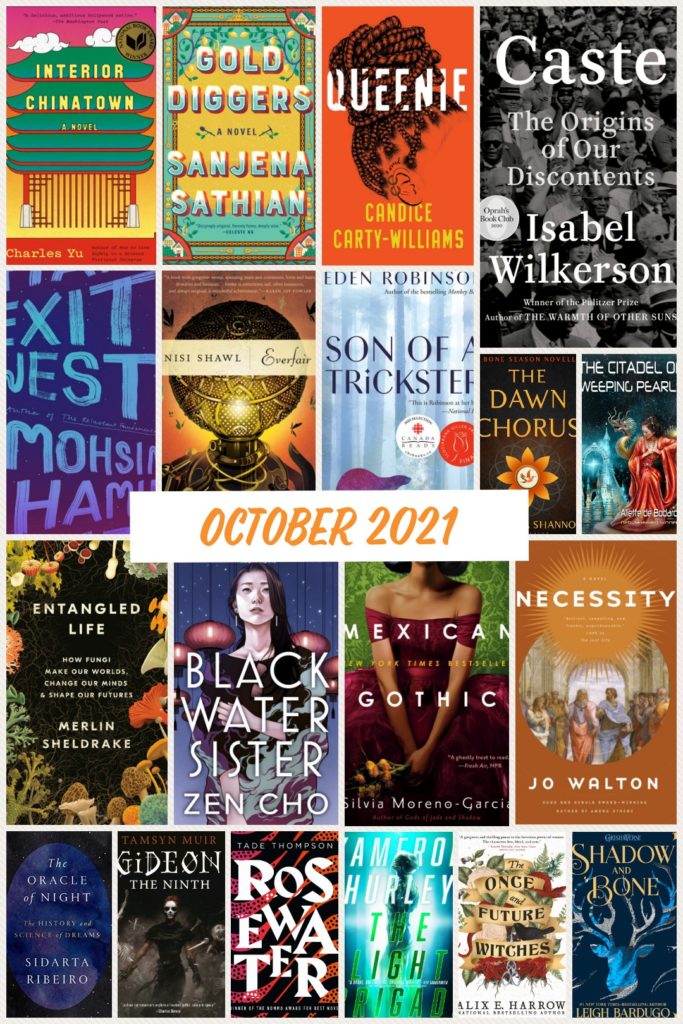

Another month, another end of month book collage! Lots of reading got done because the better half went out of town for an entire week, which meant that in the evenings there was nothing antisocial at all about my curling up and reading for 2-4 hours before bed.

The Dawn Chorus, by Samantha Shannon

Everfair, by Nisi Shawl

Entangled Life, by Merlin Sheldrake

Mexican Gothic, by Silvia Moreno-Garcia

Interior Chinatown, by Charles Yu

Shadow and Bone, by Leigh Bardugo

Black Water Sister, by Zen Cho

Gideon the Ninth, by Tamsyn Muir

Rosewater, by Tade Thompson

Exit West, by Mohsin Hamid

The Light Brigade, by Kameron Hurley

Necessity, by Jo Walton

Queenie, by Candice Carty-Williams

The Citadel of Weeping Pearls, by Aliette de Bodard

Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents, by Isabel Wilkerson

The Oracle of Night, by Sidarta Ribeiro

Gold Diggers, by Sanjena Sathian

The Once and Future Witches, by Alix E. Harrow

Son of a Trickster, by Eden Robinson