This book was published in 1989, and I think if I had read it then (or in the mid 90s, more likely), I would have been really impressed by it. The worldbuilding is next level: the planet Grass is filled with waving long grasses undulating like seas, but the residents are viscerally horrified at the idea of building roads through it, so travel is done by air car. The aristocracy gather to ride regular day-long hunts accompanied by slavering not-hounds, mounted on terrifying barbed not-horses with which they have a weird mental dependency, chasing incorporeal not-foxes that they physically rejoice in killing, but don’t bring home to eat. Despite its utter weirdness Grass seems to be the only planet not falling victim to a plague attacking humanity on every other planet, so the ruling religious organization sends a family of horse-loving ambassadors to the planet to try to make inroads with the insular aristocracy. Oh there’s also a bunch of reject priests who seem unable to convert anyone on the planet, but spend their time either climbing towers of grass for fun, or excavating evidence of a doomed alien civilization that (like humanity) apparently failed to understand Grass enough to colonize it successfully. Despite the extremely futuristic setting, the social dynamics are very gendered: both on Grass and off planet, the men have all the authority, and the women have insight but little social power. There is nothing subtle about the messaging, either; there’s a LOT of heavy-handed philosophical discussion about the place of religion and humanity’s place in the ecosystem, and the characters are sketched so obviously that it’s very clear who you are and aren’t supposed to sympathize with. There are also some truly icky bits involving nubile young women (why is it always the young women) whose minds are wiped and end up little more than mental children in problematically mature bodies. I thought the beginning was promising, especially the creepy alien atmosphere of Grass, but then everything got muddled because Tepper had so very much to say and couldn’t resist going on about it at length, or erecting more strawman villains to take down. Mixed bag overall.

Author: librarykat

Exit Strategy, by Martha Wells

Murderbot book 4 depends a little more heavily on the previous books to make sense; it does not stand alone as well as the previous ones. But it’s still really good; as Murderbot continues trying to protect its humans, it also finds it harder and harder to avoid questioning its own motives. I love that Murderbot would risk its life for a human without hesitation (scolding the human for being an idiot the entire time), but is so uncomfortable dealing with gratitude or friendship that it would rather run away than accept an overture. I loved seeing the characters from the first book come back to interact with Murderbot; their familiarity and patience with its quirks mean that it is even harder for it to turn away, even though it tries its very best.

The Outside, by Ada Hoffman

Buckle up, because this is a weird one. In a far future version of our universe, humans have built giant soul-eating AIs and now worship them as gods. Through their cybernetic post-human “angels,” the gods enforce their dictates on the people and root out any heresy, which is belief in a reality that doesn’t match the existing one. This is important because too much exposure to the “Outside” can spread like a virus, destabilizing actual reality and bringing hyperdimensional Lovecraftian horrors from Outside. In this world, autistic lesbian heroine Yasira just wants to make useful scientific inventions and hang out with her amazing girlfriend, but is unwillingly drawn into a battle between her former mentor and the AI gods for control of reality. I loved the prominent role that neurodiversity played in this book, and the recurring point that society is built on lies that we all agree on together.

Interpreter of Maladies, by Jhumpa Lahiri

A collection of short stories, about people on either side of the Indian diaspora. The writing is deceptively straightforward, with occasional flashes of artistry, almost as if Lahiri couldn’t help throwing in a gorgeous moment of description, just to show she could. It works really well. Her characters don’t really talk about their feelings in any kind of depth, but their feelings suffuse the stories, emotions seething in the unsaid. Indian immigrants come to the US and deal with the differences as best they can, sometimes finding community and sometimes not; Indian-Americans visit India and the locals wonder at their strangeness. Really nice collection, superb switching of cultural viewpoints from story to story.

In Order to Live, by Yeomi Park (with Maryanne Vollers)

Subtitled “A North Korean Girl’s Journey to Freedom,” which about covers it. I have so many thoughts but quick summary: Park’s family had a pretty middle-class existence, thanks to her father smuggling items from China, until he was caught and sent to be reeducated, throwing her, her mother, and her older sister into poverty. Faced with malnutrition and starvation and ignorant of the world, first the sister, and then the narrator and her mother, worked with people who smuggled them into China, only to fall prey to human traffickers who “married” them to Chinese men. They eventually get the help of a religious mission and made it over the Mongolian border, and were eventually shipped to South Korea and freedom. I liked her description of the indoctrination that she got from childhood, and was particularly fascinated by how it stunted her vocabulary and emotions to the point that she didn’t know the word “love” could be applied to anyone besides the Dear Leader.

The author’s told her story several times in different ways and has been criticized for changing the details of her tale, so I’m dubious of some of the specifics. However, I don’t doubt her trauma or that she suffered; I understand why she might not want to get into some of the more painful parts, or why she might have edited her memories to cast herself in a more positive light. I’ve looked her up and she’s said some things I disagree with, but I’m glad she’s finally free to speak her mind, and has the vocabulary and education to be able to advocate for what she believes to be right.

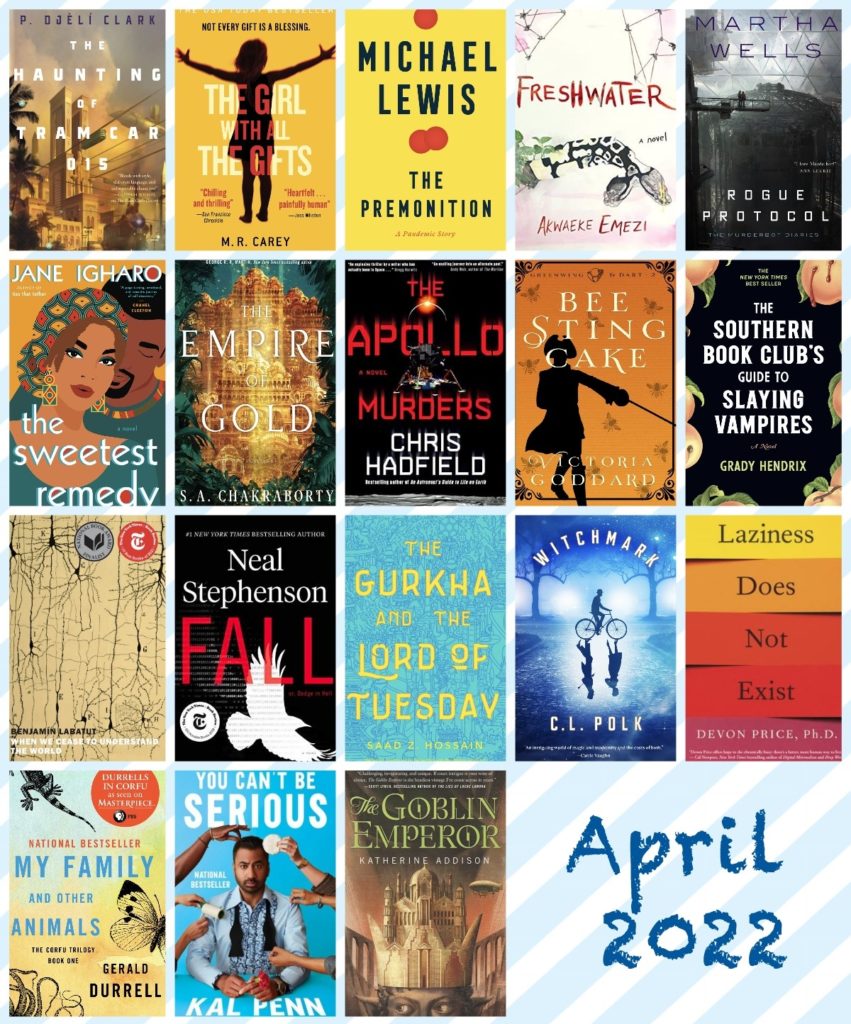

book collage for April 2022

The Haunting of Tram Car 015, by P. Djèlí Clark

The Girl with All the Gifts, by M.R. Carey

The Premonition: A Pandemic Story, by Michael Lewis

Freshwater, by Akwaeke Emezi

Rogue Protocol, by Martha Wells

The Sweetest Remedy, by Jane Igharo

The Empire of Gold, by S.A. Chakraborty

The Apollo Murders, by Chris Hadfield

Bee Sting Cake, by Victoria Goddard

The Southern Book Club’s Guide to Slaying Vampires, by Grady Hendrix

When We Cease to Understand the World, by Benjamín Labatut

Fall; or, Dodge in Hell, by Neal Stephenson

The Gurkha and the Lord of Tuesday, by Saad Z. Hossain

Witchmark, by C.L. Polk

Laziness Does Not Exist, by Devon Price

My Family and Other Animals, by Gerald Durrell

You Can’t Be Serious, by Kal Penn

The Goblin Emperor, by Katherine Addison

The Goblin Emperor, by Katherine Addison

Maia, an unwanted half-goblin (dark-skinned) unwanted son of the elf (light-skinned) emperor suddenly finds himself thrown in the deep end when his father and older brothers perish suddenly. Scarred with the early loss of his mother and the abuse of the person who raised him afterwards, he carries on doing the best he can despite his ignorance of courtly elf politics and the disadvantage of his breeding. I found this sad reading at first because of just how hurt and lonely Maia was and how much he just needed someone to give him a hug, but between that and the slow-moving, patiently developing plot, it made the eventual emotional turning points that much more rewarding. Kind of unfortunate that I read this so soon after The Hands of the Emperor, which told a similar sort of story but with way more complexity and from a different point of view; I kept wishing it were more like, which diminished my enjoyment of The Goblin Emperor through no fault of its own.

You Can’t Be Serious, by Kal Penn

Kal Penn traces his journey from theater kid in New Jersey, to film/sociology major at UCLA (to his parents’ mild dismay), to Hollywood actor, and finally to Obama’s administration in DC. Lots of discussion of racism encountered in both childhood and adulthood; nothing that would be surprising to anyone who was paying attention, but still worth acknowledging. I liked how he shone a light on how his race disqualified him from most roles, except the ones where his race was specifically called for; and even after he landed a role, the racism would continue (“ok, but can you do that with a bit more of an Indian accent? I don’t care if you don’t think it adds anything to the character, we want the stereotypical accent” type of stuff). The political part of his career was less interesting reading than the acting part, but government work in general tends to be less exciting, so no surprise there.

My Family and Other Animals, by Gerald Durrell

I picked this book up because of a stray passage from The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating, which quoted its description of snails mating “like two curious sailing ships roped together.” Upon learning that snails were hermaphroditic, the narrator’s brother said, “I think it’s unfair. All those damned slimy things wandering about seducing each other like mad all over the bushes, and having the pleasures of both sensations. Why couldn’t such a gift be given to the human race? That’s what I want to know.” When their teacher pointed out that in that case, humans would have to lay eggs, their mother chimed in with “The ideal way of bringing up a family. I wish I’d been able to bury you all in some damp earth and leave you.”

So obviously, I promptly put the book on hold,* and I am happy to say that the rest of it was equally delightful. When Gerald Durrell was a child, his eccentric family decided to escape the gloomy English weather and moved wholesale to the Greek island of Corfu, and this is his recollection of the years that his family (hilariously and charmingly sketched) spent in that Mediterranean paradise. Gerald, an enthusiastic young naturalist, was mostly allowed to run wild over the island and study nature to his heart’s content; he brought back to his house a collection of birds, insects, and other creatures. Durrell’s loving portraits of animals and nature are adorable but a bit long-winded; it’s when he works in stories of his family and their ridiculous antics that the book really shines. Apparently his books were made into a BBC series called The Durrells in Corfu; I would love to look that up sometime.

*It turned out that the snail bit was not actually from this book, but from the sequel, Birds, Beasts, and Relatives, which was not available from my library. Fortunately, a preview was included at the end, so I was able to find this section after all.

Laziness Does Not Exist, by Devon Price

I came hoping for a nuanced critique of workaholic capitalism, and got positivity and compassion instead. Like most self-help books, this one can be summed up in a short paragraph, but it’s padded out with a ton of personal stories that Price hopes will resonate with you. The summary: the American workaholic culture makes you feel bad for taking time out for yourself, but don’t let that stop you! Taking breaks will stave off burnout, refresh your mind, rejuvenate your system, and make you a more productive person overall. The book is very geared towards a certain type of white-collar salaried worker with benefits, or maybe an overworked stay-at-home spouse being supported by their partner’s salary, who can afford to advocate for changes on their own behalf without fear of dismissal. There was passing acknowledgement of people working multiple jobs on the gig economy, but critique was directed more at the cultural/psychological pressure to stay busy and productive than any actual financial need, which I feel is rather dismissive of anyone who takes those jobs to make ends meet. Finally, the title is annoyingly incorrect; Price’s point is that laziness should not be a cultural negative, not that it doesn’t exist at all.