This is an autobiographical piece written like poetry, which Vuong frames as a letter to his illiterate mother. The writing is gorgeous and heartbreaking; Vuong’s mother is shown lashing out at her young son in one moment, and then her own generational trauma as a war refugee is explored in the next. It’s not an excuse, but an exploration of root causes. Nothing needs to be explained if it’s all out there for you to see. Vuong peppers his experiences with those of his mother’s and grandmother’s, letting us see the impact of racism, class tension, and trauma across generations. He approaches his own experience with love similarly, letting us see his boyfriend in moments of both sweetness and toxic masculinity, showing us just enough of his background to help us recognize him as a product of his surroundings. Vuong has a beautiful deftness with words, and uses them to show how the people in his story manage to communicate love without using words at all.

Author: librarykat

Untethered Sky, by Fonda Lee

I enjoyed this novella, but I think Lee was so taken by her concept that she neglected character building in favor of general coolness. Narrator Ester narrowly escaped a manticore attack that took half her family; her life became laser-focused towards joining the king’s mews, where rukhers tame and fly the giant rocs that are the kingdom’s only defense against the manticores. The core of the book is the dynamic between Ester’s complete devotion to her roc, and the knowledge that the roc is utterly unmoved by her affection or loyalty. The story makes occasional halfhearted forays into politics and propaganda, but Ester’s unwavering dedication to manticore murder gives her character very little room to grow. Pleasant read with very cool giant bird details, but does not feel like a complete story.

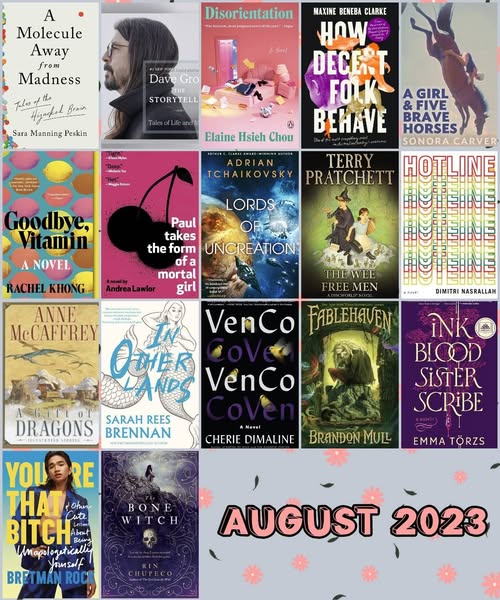

book collage, August 2023

I finally wrote the last book review and can post the collage for August! It’s been a busy couple of weeks. My recent habit of reading yet more books to escape from the self-inflicted pressure of writing book reviews has… not helped.

A Molecule Away from Madness: Tales of the Hijacked Brain, by Sara Manning Peskin: Through a selection of case studies written like medical mysteries, neurologist Peskin illustrates the terrifying effects of the tiniest changes: from the gene-directed protein synthesis that results in Huntington’s chorea, to a woman whose own immune system flooded her brain with hallucinogens, to a patient whose grip on reality was threatened by what turned out to be a simple vitamin deficiency, this book left me amazed at the delicate balance our bodies must tread to maintain our brains.

The Storyteller, by Dave Grohl: Came for the rock’n’roll stories from an artist whose music I enjoy; stayed for the self-deprecating humor, unashamed fanboying, and poignant, heartfelt stories from a man who never stopped being grateful for the improbable delights in his life. Grohl grew up in northern Virginia, so I was able to identify both with his childhood memories of the DC area as well as his feelings of recognition and homecoming every time he returned. I particularly liked listening to him narrate the audiobook; his enjoyment of storytelling was palpable and a delight to the listener.

Disorientation, by Elaine Hsieh Chou: Oh man if you thought Yellowface was a vicious takedown of racism in publishing, wait until you read Disorientation, which does the same thing to academics but multiplies it by ten. The main character, Ingrid Yang, is in the middle of a dissertation she hates, a deep dive into the works of famous poet Xiao-Wen Chou. One day, a chance find in the archives sends her into a deep dive into Chou’s history and a bombshell of a discovery that upends everything Ingrid thinks she knows, expanding to include her own conception of herself, her race, and her relationships. Neurotic, self-doubting Ingrid is contrasted against her confident best friend Eunice Kim, as well as her rage-filled rival Vivian Vo; the way the three women choose to conceive of, and express, their Asian-Americanness provides an undercurrent of identity exploration to the race-related ripples caused in the larger society around them by Ingrid’s discovery. The satire in this book is incredibly heavy-handed but the zingers keep landing, so you keep reading.

How Decent Folk Behave, by Maxine Beneba Clarke: An incredibly powerful collection of poetry from Clarke, an Australian poet of Afro-Caribbean descent. The poems center the reader in Clarke’s world and viewpoint, a place where women and people of color have it hard; even as she paints that world in heartbreaking detail, she colors it with her fierce resolve to fight back, to stand together, to grow strong. The title is actually a line from the poem “something sure,” in which a Black mother sits her son down and tells him to pay attention: she is raising him to be a good man, one who knows “how decent folk behave,” but he needs to know: there are times when other men can be a danger to women, and when those times arise, she needs her son to be the kind of man who will step in, to intervene as only a fellow man can. It’s chilling, poignant, and beautiful.

A Girl and Five Brave Horses, by Sonora Carver: In 1923, then-teenage Sonora answered an ad by William Carver looking for a “diving girl” to ride a horse as it plunged 11 feet from a tall platform into a pool of water. She ended up joining Carver’s traveling entertainment act, performing around the country, and eventually marrying Carver’s son. In 1931, she hit the water wrong during a dive and suffered retinal detachment, eventually going blind; despite that, she continued to dive horses until their show ended when war broke out in 1942. The writing style of the book is straightforward and simplistic, with Carver demonstrating classic 1920s “spunky girl” attitude – unafraid to speak her mind, but always acknowledging that the men around her had the power and she had to persuade them before she could have her way. I was particularly interested by her detailed description of how both girls and horses were trained to dive (only a few actually took to the training; she makes it clear that in her time with the show, no girl or horse was ever pushed beyond their comfort zone), and the construction of the diving platform and pool. Her account of her blindness and how she dealt with it (and how she preferred others to treat her) is actually a great section on dealing with disability from someone who never had to consider the issue before.

Goodbye, Vitamin, by Rachel Khong: I honestly wasn’t grabbed by the book at first, but as I read, I slowly became invested. Ruth, escaping from a failed engagement and tepid career, returns home for the holidays and finds herself sticking around to help her mother care for her father, whose dementia is worse than Ruth had realized. Ruth finds herself settling into the mundanity of basing her father’s diet off of online nutrition research, slowly mending fences with her mother, and colluding with a pack of her father’s former university students to create for him the illusion of a normal life. Interspersed with the story are her father’s journal entries from when he was besotted with her as a child; I like how they reflected the role reversal now taking place between them.

Paul takes the form of a mortal girl, by Andrea Lawlor: Paul Polydoris is a queer teenage bartender in a college town in 1993; he can change the shape of his body at will and frequently does, assuming whatever shape and gender that will get him laid (which is depicted quite graphically). After romping his way through various parts of the queer scene, Paul takes on the form of “Polly” and accompanies his friend to a lesbian retreat, where he falls in love with a girl named Diane and eventually follows her to San Francisco. Paul is filled with an intense longing to belong to someone and to give them his whole heart; at the same time; he chafes at being restricted to just one form and one role, restlessly changeable both outside and in. With such a mutable character it’s hard to have any kind of growth arc, and indeed, the lack of any kind of arc was one of the worst things about this story. Without any particular self-reflection on Paul’s part, his endless sexual escapades began to feel like just another part of the character he was performing, each encounter yet another experience he wasn’t learning from. I can’t tell if this book is a love letter to the queer scene of the early 90s, or a condemnation of the fact that the scene seemed to force people into rigid gender roles. Maybe, like the protagonist, the author also wants to have it both ways.

Lords of Uncreation, by Adrian Tchaikovsky: I was so excited to read this conclusion to Tchaikovsky’s Final Archtecture trilogy and it absolutely did not disappoint (except when I reached the end and realized that I wouldn’t be spending any more time with these characters). It’s classic space opera with an extremely existential threat to humanity (and humanity’s various alien sometime-allies), with plenty of facets looking out only for themselves. As usual with Tchaikovsky’s novels, no matter how weird things get, it’s the beautiful character work that pulls the reader along; most of the arcs end well, and some end excellently.

The Wee Free Men, by Terry Pratchett: For some reason I never read the Tiffany Aching subset of the Discworld books, so when I saw this volume at the used book store, I picked it up for the kid. He absolutely loved it and demanded more (dear Libraries ACT, you need to stock up). Tiffany is an excellent version of the practical Pratchett heroine; she pushes back aginst dogma, does her own research, and forges ahead with determination. The Wee Free Men are excellent supporting characters, as are Tiffany’s fellow countrymen. Fine middle-grade reading material, entertaining without being dogmatic.

Hotline, by Dimitri Nasrallah: This book was tearing up the review scene in Canada so I gave it a shot. The pace is slow and patient, mostly moving through mundane details and only hinting at the broader picture, but builds on itself until the smallest actions carry huge emotional weight. Muna is a Lebanese immigrant teacher whose French skills are not as useful as she had hoped they would be in Montreal; to support herself and her son Omar, she takes a job at a call center selling a weight loss program. It’s hard scrabbling out a living as a single mom in the Montreal winter, but in Muna’s life, the small victories and occasional moments of grace balance out the casual racism and institutional disregard. The gradual unfolding of the events in Lebanon that drove her to Montreal are illuminating as well. Really well done storytelling.

A Gift of Dragons, by Anne McCaffrey: The kid read Dragonsong and liked it, so I went looking for more Pern material that might be suitable for young adults. This short story collection isn’t it; the stories cover bullying (The Smallest Dragonboy), reinforcing traditional gender roles (Ever the Twain), and deep dives into the series and society of Pern which I don’t feel like dragging the kid into (The Girl who Heard Dragons, Runner of Pern). Pern was a huge part of my adolescence but I feel like it might not be aging well; certainly there’s better stuff out there these days.

In Other Lands, by Sarah Rees Brennan: Excellent book, I want to push it at all misfit teenagers (and the adults they grow up to be). It’s a self-aware portal fantasy, done super well. 13 year old Elliot, upon discovering that he can enter a magical world, immediately tries to improve it: he smuggles in ballpoint pens to use instead of quills, calls out cross-species racism, and promotes diplomacy over war. His changing relationships with his warrior peers, elf Serene and awkward scion Luke, work as a beautiful heart to the story. (Fans of the relationship dynamic in Naomi Novik’s Scholomance series will enjoy this one too.) I couldn’t wait to finish this book and also never wanted it to end.

VenCo, by Cherie Dimaline: I wanted to like this more than I actually did; the concept was great but the execution was heavy-handed and the plot essentially went nowhere. Six out of seven witches in a coven have come together, and a two-dimensional evil witchhunter (thinly veiled symbol of the patriarchy) has ramped up his efforts to hunt down the last witch before she can join them and bring about some nebulous prophesied change. The witches, who have all escaped some form or other of sexist sadness, don’t seem to have gained any particular magic from their having done so; the ones with magic seem to have had it already. Basically this was super girls-against-the-man! women have ancient and mysterious powers! which I would ordinarily be down with but there should really have been a lot more thinking going into plotting, worldbuilding, and character arcs. I stubbornly made it to the end and the payoff was… less than worth it.

Fablehaven, by Brandon Mull: Delightfully creepy but not too scary at any given time, which is a great balance to strike. Cautious, law-abiding Kendra and her impulsive brother Seth are dropped off at their grandparents’ for the summer; their grandfather Stan seems less than happy with this arrangement, and the children soon find out why, setting themselves up for a summer of magic, adventure, and plenty of opportunities for desperate bravery. I liked how both child and adult characters were given space to both make mistakes and learn from them, in a way that felt organic to the story and not forced. No particularly new ideas here, but very smoothly executed. Ties up the biggest conflicts at the end, but leaves lots of nice open ends for sequels.

Ink Blood Sister Scribe, by Emma Törzs: Kudos to this book for not only being well-plotted and well-executed, but also having one of the best as-needed reveals of magic systems I’ve read in a while. The main characters are estranged sisters Esther, who left home at age 18 and never returned; and Joanna, who remained a faithful protector of their family’s library of magical books. Across the ocean, there’s also Nicholas, a Scribe whose inborn magic allows him to write more of those books, though at a severe cost to his health. Eventually, all three of them stumble together into the realization that there is way more to their separate situations than they were ever allowed to understand. Great pacing and smooth writing made this a very satisfying read.

You’re That Bitch, by Bretman Rock: I’ll be honest, my decision process for picking up this book consisted solely of “hey! That gorgeous genderfluid model on the cover of Vogue Philippines also wrote a book?” I expected to put this down after no more than thirty seconds, but instead I got sucked into a fascinating story of a life spent first in the Philippines, then in Hawaii, in the care of a large, rambunctious family that was sometimes problematic but always fully supportive. I loved the depictions of his family, particularly his grandmother, mother, and sister, and their Filipino customs; it was also really interesting to read about his journey from baby influencer to self-made star. The tone of the book is light, jammed with interjections like “girl” and “yenno,” feels like he narrated it voice-to-text, and generally made me feel very old; it’s easy to skim (and I did in fact skim past most of the encouraging self-help bits at the end of each chapter) and quick to read.

The Bone Witch, by Rin Chupeco: This book begins with a woman raising demons from skeletons, as a timid bard creeps up and begins gently drawing her story out of her; in turn, she divulges details about him that she should not know. By all rights it should have ended with their stories meeting together at the present, then proceeding together into a satisfying climax… but as her story dragged on and on, crammed with irrelevant detail and bloated with extraneous characters, I reached page 668 of 714 and realized that there was no way in this book we were going to reach the end of her story. Epic battles and inter-kingdom wars had been hinted at, and she’d barely graduated school. I felt extremely cheated and in no mood to read any further in the series. I was also not a fan of her culture, in which women with magic powers were required to train as warrior-geishas who could sing, dance, kick butt, and still simper and giggle around powerful men while entertaining them. Seriously. Meanwhile male magic-users have to join a killing squad with a high death rate. I was briefly interested when a male magic-using character showed up and wanted to train as a geisha, but we never learn where his story goes because 700 pages later we’re only a fraction done with the story. Definitely not continuing on. (Unless someone tells me it gets more worthwhile.)

We Were Liars, by E. Lockhart

Points to Lockhart for making you feel sorry for the narrator right off the bat. She’s a poor little rich girl, but her inner pain is vividly portrayed as physical: imaginary knives sink into her skin, objects cleave open her brain, and as blood and viscera pour over her clothes her mother tells her to stand straight and look calm… so she pulls herself together, and does as she is told. As the book goes on, it’s hard to distinguish reality from internal metaphor, but as the clues pile up you begin to understand the origins of her mental disturbance, as well as the ghosts that haunt her wealthy family. The writing style was full of sentence fragments and occasional mid-sentence line breaks; it could have been awkward, but settled quite nicely into the rhythm of stream-of-consciousness narration. Pretty bravely experimental for YA, all things considered.

An Enchantment of Ravens, by Margaret Rogerson

In the town of Whimsy, elves exchange magic for items of human craft; often, the magic has a dark side. Painter Isobel has learned to be very precise with her dealings with elves, but one day makes a mistake by painting a mortal emotion that she sees in the eyes of Rook, the autumn prince. He demands that she appear in his court to answer for her crime; however, during their journey they find that things have gone very wrong in the elven lands. I really loved Rogerson’s elves, who are prickly, vain, and superficial but in their hearts crave the touching, transient beauty of mortality; I also loved Isobel’s defiant embrace of her own humanity. I rolled my eyes a bit at the relationship between Isobel and Rook, but by the end of the book could not imagine them any other way. Surprisingly good; the book just got better as it went along.

The Bone Witch, by Rin Chupeco

This book begins with a woman raising demons from skeletons, as a timid bard creeps up and begins gently drawing her story out of her; in turn, she divulges details about him that she should not know. By all rights it should have ended with their stories meeting together at the present, then proceeding together into a satisfying climax… but as her story dragged on and on, crammed with irrelevant detail and bloated with extraneous characters, I reached page 668 of 714 and realized that there was no way in this book we were going to reach the end of her story. Epic battles and inter-kingdom wars had been hinted at, and she’d barely graduated school. I felt extremely cheated and in no mood to read any further in the series. I was also not a fan of her culture, in which women with magic powers were required to train as warrior-geishas who could sing, dance, kick butt, and still simper and giggle around powerful men while entertaining them. Seriously. Meanwhile male magic-users have to join a killing squad with a high death rate. I was briefly interested when a male magic-using character showed up and wanted to train as a geisha, but we never learn where his story goes because 700 pages later we’re only a fraction done with the story. Definitely not continuing on with this series. (Unless someone tells me it gets more worthwhile.)

You’re That Bitch, by Bretman Rock

I’ll be honest, my decision process for picking up this book was “hey! That gorgeous genderfluid model on the cover of Vogue Philippines also wrote a book?” I expected to put this down after no more than thirty seconds, but instead I got sucked into a fascinating story of a life spent first in the Philippines, then in Hawaii, in the care of a large, rambunctious family, sometimes problematic but always fully supportive. I loved the depictions of his family, particularly his grandmother, mother, and sister, and their Filipino customs; it was also really interesting to read about his journey from baby influencer to self-made star. The tone of the book is light, jammed with interjections like “girl” and “yenno,” feels like he narrated it voice-to-text, and generally made me feel very old; it’s easy to skim (and I did in fact skim past most of the encouraging self-help bits at the end of each chapter) and quick to read.

Ink Blood Sister Scribe, by Emma Törzs

Kudos to this book for not only being well-plotted and well-executed, but also having one of the best as-needed reveals of magic systems I’ve read in a while. The main characters are estranged sisters Esther, who left home at age 18 and never returned; and Joanna, who remained a faithful protector of their family’s library of magical books. Across the ocean, there’s also Nicholas, a Scribe whose inborn magic allows him to write more of those books, though at a severe cost to his health. Eventually, all three of them stumble together into the realization that there is way more to their separate situations than they were ever allowed to understand. Great pacing and smooth writing made this a very satisfying read.

Fablehaven, by Brandon Mull

Delightfully creepy but not too scary at any given time, which is a great balance to strike. Cautious, law-abiding Kendra and her impulsive brother Seth are dropped off at their grandparents’ for the summer; their grandfather Stan seems less than happy with this arrangement, and the children soon find out why, setting themselves up for a summer of magic, adventure, and plenty of opportunities for desperate bravery. I liked how both child and adult characters were given space to both make mistakes and learn from them, in a way that felt organic to the story and not forced. No particularly new ideas here, but very smoothly executed. Ties up the biggest conflicts at the end, but leaves lots of nice open ends for sequels.

VenCo, by Cherie Dimaline

I wanted to like this more than I actually did; the concept was great but the execution was heavy-handed and the plot essentially went nowhere. Six out of seven witches in a coven have come together, and a two-dimensional evil witchhunter (thinly veiled symbol of the patriarchy) has ramped up his efforts to hunt down the last witch before she can join them and bring about some nebulous prophesied change. The witches, who have all escaped some form or other of sexist sadness, don’t seem to have gained any particular magic from their having done so; the ones with magic seem to have had it already. Basically this was super girls-against-the-man! women have ancient and mysterious powers! which I would ordinarily be down with but there should really have been a lot more thinking going into plotting, worldbuilding, and character arcs. I stubbornly made it to the end and the payoff was… less than worth it.