This is the second Hendrix book that I read that came highly recommended, the second time I thought I’d enjoy reading it, and the second time I’ve been disappointed. It’s just not for me, sorry guys. I think that completely aside from the body horror / jump scare aspects which are already not my thing, the root of my issues with Hendrix’s books is that he seems actively contemptuous of his characters. The main characters are all flat and unlikeable, and their motivations and emotions seem sketched over them as opposed to growing naturally out of their personalities. In contrast I’d offer Stephen King, who has all the dark and creepy but seems actually to generate characters from a place of strength and humanity, thereby giving readers a reason to actually care what happens to them. It really feels like Hendrix is creating characters he doesn’t like, just so he can point at them and laugh, and the whole thing just feels a bit mean-spirited. (This is also exactly why I don’t enjoy watching Big Bang Theory.) Plot synopsis, so I can reference it later: unlikeable, shallow main character’s parents die, which means she has to cooperate with her equally unlikeable, shallow sibling to rid the house of elements from her parents’ haunted past, so they can finally sell it and reap the benefits of the inheritance, to which each feels more entitled than the other.

Author: librarykat

A Taste of Gold and Iron, by Alexandra Rowland

This is a super cute prince-and-warrior queer romance fantasy that feels like it was also written by an economics nerd. Prince Kadou, extremely insecure and given to panic attacks, gets into hot water and his sister the queen must exile him from court. Evemer, one of the royal family’s scholar-bodyguards, reluctantly accepts the duty of guarding the flighty prince, and they find themselves investigating a mystery involving political scheming and counterfeit currency. The currency bit is particularly relevant because Kadou, like certain others in the kingdom, has the ability to tell the purity of a metal by touch, a fact integral to guaranteeing the trustworthiness of his country’s currency (and which makes the issue of counterfeits particularly fraught). I liked the romance, but I loved the worldbuilding.

The Burning Sky, by Sherry Thomas

Solid YA fantasy, refreshing gender twists. Heroine Iolanthe ignores her guardian and puts on a showy display of magic, which immediately makes her a target of the dictator-king’s secret police. She is rescued by an exiled prince, who has been preparing for the appearance of a prophesied elemental mage. Undeterred by her gender, he promptly installs her in the spot which he’d prepared for a fellow student in the decidedly nonmagical and male-only Eton, and proceeds to train her in magical skill and combat. Solid series beginning, and I like how the main characters approach each other as equals despite their differences in gender, rank, and magical power.

Ithaca, by Claire North

The story of Penelope, told by Hera, which is an interesting choice. As in classical Greek mythology, Hera is full of rage and indignation but mostly helpless to actually accomplish anything. She skulks around the edges of events, a bitterly perceptive witness to the goings-on in Ithaca in Odysseus’s absence, affecting events as much as she dares while trying not to draw the attention of the more powerful gods and goddesses. The writing in this is pretty excellent, as is the characterization of the various mythological figures, but mostly this story is a frustrating series of examples of the lack of power and agency of women, even goddesses and queens.

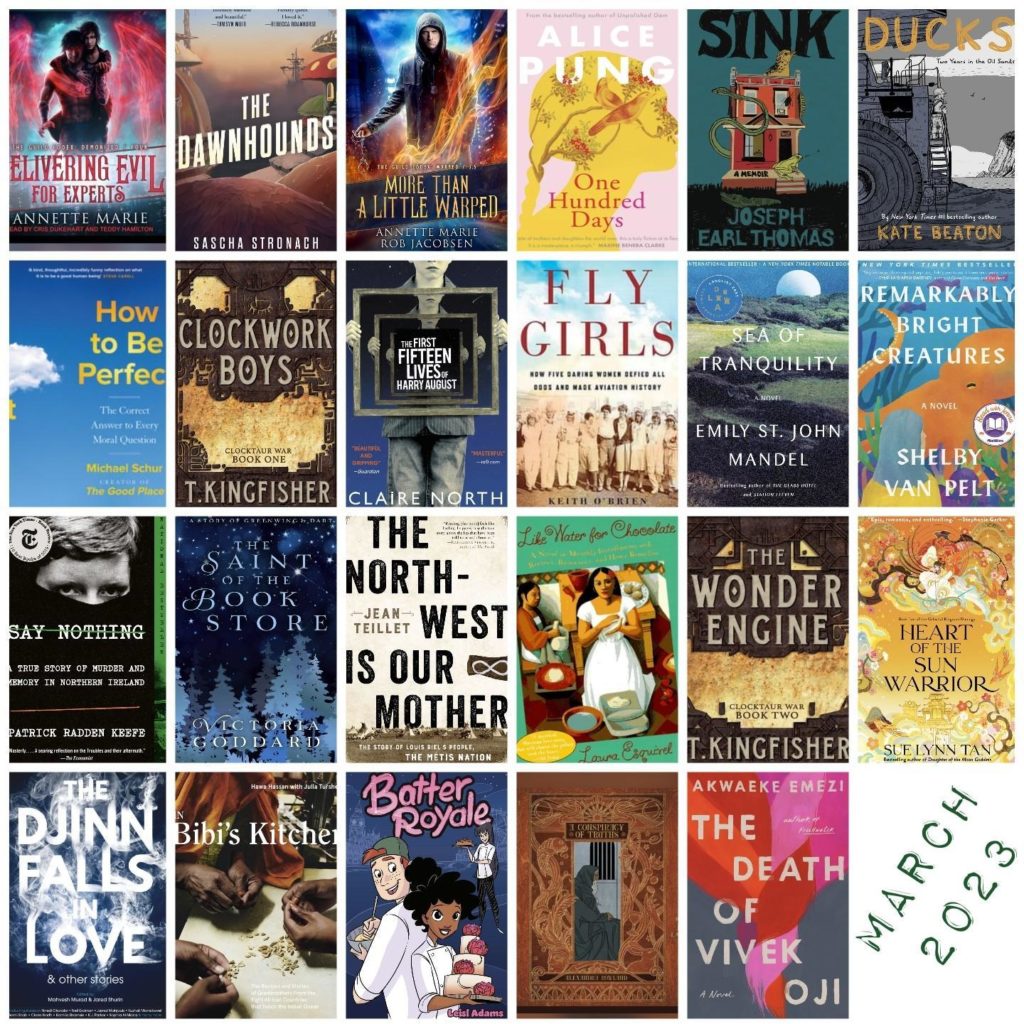

book collage, March 2023

March was a really heavy reading month, both in terms of volume and content; between the glass ceiling facing early women aviators, the abuse of the Métis nation by the Canadian government, the Troubles in Northern Ireland, and the soul-deadening misogyny that Kate Beaton faced in the Alberta oil sands*, I was pretty down on humanity in general. But the books were awesome and also thank goodness for plenty of happy escapist fiction with which to pass the time. I’ll take it easier next month. (Especially since it’ll be fall break for the kids’ school.)

* Beaton’s book just won Canada Reads though, so I guess that counts for something! Well deserved.

Delivering Evil for Experts, by Annette Marie, read by Cris Dukehart

The Dawnhounds, by Sascha Stronach

More than a Little Warped, by Annette Marie and Rob Jacobsen

One Hundred Days, by Alice Pung

Sink: A Memoir, by Joseph Earl Thomas

Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands, by Kate Beaton

How to be Perfect: The Correct Answer to Every Moral Question, by Michael Schur

Clockwork Boys, by T. Kingfisher

The First Fifteen Lives of Harry August, by Claire North

Fly Girls: How Five Daring Women Defied All Odds and Made Aviation History, by Keith O’Brien, read by Erin Bennett

Sea of Tranquility, by Emily St. John Mandel

Remarkably Bright Creatures, by Shelby Van Pelt

Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland, by Patrick Radden Keefe, read by Matt Blamey

The Saint of the Bookstore, by Victoria Goddard

The North-West is our Mother: The Story of Louis Riel’s People, the Métis Nation, by Jean Teillet

Like Water for Chocolate, by Laura Esquivel

The Wonder Engine, by T. Kingfisher

Heart of the Sun Warrior, by Sue Lynn Tan

The Djinn Falls in Love & Other Stories, ed. Mahvesh Murad, Jared Shurin

In Bibi’s Kitchen: The Recipes and Stories of Grandmothers from the Eight African Countries That Touch the Indian Ocean, by Hawa Hassan with Julia Turshen

Batter Royale, by Liesl Adams

A Conspiracy of Truths, by Alexandra Rowland, read by James Langton

The Death of Vivek Oji, by Akwaeke Emezi

The Death of Vivek Oji, by Akwaeke Emezi

Emezi’s previous novel Freshwater was such an emotional slog that I put off reading this one for a while. Turns out it’s the opposite: a focused, sharp stab of a story that knows exactly where it’s going and what it wants to say. It spirals towards the central fact of Vivek’s death by flipping back and forth between accounts, tales told by various friends, family, or acquaintances. The stories, told both in present or past tense, slowly contribute to the bigger narrative until the reader is finally granted a complete picture of Vivek, the people and the emotions around him, and how everything led inexorably to his fate. Vivek belonged to a community of children born to the Nigerwives, non-Nigerian women who married Nigerian men, and it is their attitudes that help set up some of the culture clash around the concepts of gender, sexuality, and identity, and the danger of trying to live one’s truth in a community where riots and violence seem always just a breath away.

A Conspiracy of Truths, by Alexandra Rowland, read by James Langton

This book had one of the best beginnings I’ve ever read, followed by one of the slowest and most boring middles, before it ramped slowly upwards towards a pretty decent ending. This is another Thousand and One Nights type nested-stories book, except the storyteller is a crochety old man, unjustly imprisoned in a foreign country, whose only friend is his extremely sweet and naive apprentice, and whose only weapon is the vast library of stories in his brain. From his prison cell, he grasps at any bits of news of the outside world that he can get, slowly weaving them into an almost unbelievable escape plan. This book has a lot to say about stories, about the stories that we tell ourselves both individually and collectively, and how we use them to shape our lives and our fates. It’s a truly interesting framing device, but personally I got tired of the narrator pretty quickly; he’s extremely unlikeable and makes very questionable decisions, and you never get to leave his head. I did love the cast, which included a lot of extremely strong female characters (though not many of them were likeable either). There was a lot of politics and it was a bit difficult to keep track of all the players; also, some of the stories were clearly meant to convey an underlying point but that point was often lost on me. I eventually made it through (as does the storyteller, who obviously lives to tell the tale) but, like the storyteller, I also feel like I suffered unduly in the process. I recommend the audiobook; Langton does a very good grumpy old man and it’s probably thanks to his narration that I got through the boring bits of the book at all (I would likely have abandoned a print copy partway through). The oral storytelling format also works really well with the first-person narration.

Batter Royale, by Liesl Adams

Cute little graphic novel about Rose, a young Canadian waitress who loves baking but can’t afford culinary school. One day a food critic tastes her baking and invites her to a reality show baking competition; of course she jumps right in. The book is definitely for younger folk; Rose’s sweetness is always rewarded, her antagonist is cartoonishly evil, any argument she has with her partner is swiftly resolved, and it’s amusing to think of how many lawsuits would be filed against the producers of the baking competition in the real world. A generally adorable read, interspersed with cheerfully illustrated recipes. I might even try to make some of the maple-infused desserts someday.

In Bibi’s Kitchen: The Recipes and Stories of Grandmothers from the Eight African Countries That Touch the Indian Ocean, by Hawa Hassan with Julia Turshen

Each chapter of this cookbook opens with a quick rundown of the particular African country, followed by profiles of grandmothers (bibis) from that country, and those little interviews are the heart of this book. Their stories help the food come to life not just as recipes, but as parts of their lives and their cultures. My favorite question in the interviews was always “Why did you choose to make ____ to share with us?” because the answers were always so adorable: usually because it was a traditional food, but also “because it’s an easy weeknight meal and my kids love it,” or “everyone always compliments me when I make this dish for gatherings.” It adds so much more context to the recipe to imagine it as a weekday staple for a big family, or as an often-anticipated party dish. There aren’t a lot of African cookbooks out there in the Western world, much less African home cooking from specific countries, so this book definitely stands out in the genre; also, the bibi angle made it just incredibly sweet to read. I loved also that the authors found bibis to interview not just in their native countries, but also women whose journeys took them to foreign countries where they still found ways to cook the food of their people. The book is also written with a Western audience in mind; ingredient substitutions are helpfully offered in multiple places in the book, as well as very practical cooking and serving suggestions. My favorite bit in one recipe was clearly an adorable interjection by a worried bibi: a caution to be careful when handling hot things; in her country they have “kitchen hands” but Westerners should use oven mitts. Adding this to my list of books to get hardcopies of when we finally settle down.

The Djinn Falls in Love & Other Stories, ed. Mahvesh Murad, Jared Shurin

There are some big names in here (Nnedi Okorafor, Neil Gaiman) and some that I love but may not be so famous (Amal El-Mohtar, Claire North, Saad Z. Hossain), but for me the standout stories were by authors I hadn’t previously encountered. “Reap” by Sami Shah is written from the viewpoint of a drone operator who is surveilling the Pakistan-Afghanistan border, and who begins to witness some freaky supernatural goings-on. It’s brilliant, combining frightening djinn behavior with the weird disconnection of war at a distance, and the feeling of being under threat by forces you can’t comprehend. I’d give second place to “The Congregation” by Kamila Shamsie, a gorgeous and spiritual piece about longing and brotherhood. Honorable mention to “Duende 2077” by Jamal Mahjoub, in which an exorcist is called to visit a haunted spaceship. Mostly a strong collection, put together in a way that started out whimsical and got really creepy towards the end.