Paul Polydoris is a queer teenage bartender in a college town in 1993; he can change the shape of his body at will and frequently does, assuming whatever shape and gender that will get him laid (which is depicted quite graphically). After romping his way through various parts of the queer scene, Paul takes on the form of “Polly” and accompanies his friend to a lesbian retreat, where he falls in love with a girl named Diane and eventually follows her to San Francisco. Paul is filled with an intense longing to belong to someone and to give them his whole heart; at the same time; he chafes at being restricted to just one form and one role, restlessly changeable both outside and in. With such a mutable character it’s hard to have any kind of growth arc, and indeed, the lack of any kind of arc was one of the worst things about this story. Without any particular self-reflection on Paul’s part, his endless sexual escapades began to feel like just another part of the character he was performing, each encounter yet another experience he wasn’t learning from. I can’t tell if this book is a love letter to the queer scene of the early 90s, or a condemnation of the fact that the scene seemed to force people into rigid gender roles. Maybe, like the protagonist, the author also wants to have it both ways.

Month: August 2023

Goodbye, Vitamin, by Rachel Khong

I honestly wasn’t grabbed by the book at first, but as I read, I slowly became invested. Ruth, escaping from a failed engagement and tepid career, returns home for the holidays and finds herself sticking around to help her mother care for her father, whose dementia is worse than Ruth had realized. Ruth finds herself settling into the mundanity of basing her father’s diet off of online nutrition research, slowly mending fences with her mother, and colluding with a pack of her father’s former university students to create for him the illusion of a normal life. Interspersed with the story are her father’s journal entries from when he was besotted with her as a child; I like how they reflected the role reversal now taking place between them.

A Girl and Five Brave Horses, by Sonora Carver

In 1923, then-teenage Sonora answered an ad by William Carver looking for a “diving girl” to ride a horse as it plunged 11 feet from a tall platform into a pool of water below. She ended up joining Carver’s traveling entertainment act, performing around the country, and eventually marrying Carver’s son. In 1931, she hit the water wrong during a dive and suffered retinal detachment, eventually going blind; despite that, she continued to dive horses until their show ended when war broke out in 1942. The writing style of the book is straightforward and simplistic, with Carver demonstrating classic 1920s “spunky girl” attitude – unafraid to speak her mind, but always acknowledging that the men around her had the power and she had to persuade them before she could have her way. I was particularly interested by her detailed description of how both girls and horses were trained to dive (only a few actually took to the training; she makes it clear that in her time with the show, no girl or horse was ever pushed beyond their comfort zone), and the construction of the diving platform and pool. Her account of her blindness and how she dealt with it (and how she preferred others to treat her) is actually a great section on dealing with disability from someone who never had to consider the issue before.: A Girl and Five Brave Horses, by Sonora Carver

How Decent Folk Behave, by Maxine Beneba Clarke

An incredibly powerful collection of poetry from Clarke, who is an Australian poet of Afro-Caribbean descent. The poems center the reader in Clarke’s world and viewpoint, a place where women and people of color have it hard; even as she paints that world in heartbreaking detail, she colors it with her fierce resolve to fight back, to stand together, to grow strong. The title is actually a line from the poem “something sure,” in which a Black mother sits her son down and tells him to pay attention: she is raising him to be a good man, one who knows “how decent folk behave,” but he needs to know: there are times when other men can be a danger to women, and when those times arise, she needs her son to be the kind of man who will step in, to intervene as only a fellow man can. It’s chilling, heartbreaking, and beautiful.

Disorientation, by Elaine Hsieh Chou

Oh man if you thought Yellowface was a vicious takedown of racism in publishing, wait until you read Disorientation, which does the same thing to academics but multiplies it by ten. The main character, Ingrid Yang, is in the middle of a dissertation she hates, a deep dive into the works of famous poet Xiao-Wen Chou. One day, a chance find in the archives sends her into a deep dive into Chou’s history and a bombshell of a discovery that upends everything Ingrid thinks she knows, including about her own conception of herself, her race, and her relationships. Neurotic, self-doubting Ingrid is contrasted against her confident best friend Eunice Kim, as well as her rage-filled rival Vivian Vo; the way the three women choose to conceive of, and express, their Asian-Americanness provides an undercurrent of identity exploration to the race-related ripples caused in the larger society around them by Ingrid’s discovery. The satire in this book is incredibly heavy-handed but the zingers keep landing, so you keep reading.

The Storyteller, by Dave Grohl

Came for the rock’n’roll stories from an artist whose music I enjoy; stayed for the self-deprecating humor, unashamed fanboying, and poignant, heartfelt stories from a man who never stopped being grateful for the improbable delights in his life. Grohl grew up in northern Virginia, so I was able to identify both with his childhood memories of the DC area as well as his feelings of recognition and homecoming every time he returned. I particularly liked listening to him narrate the audiobook; his enjoyment of storytelling was palpable and a delight to the listener.

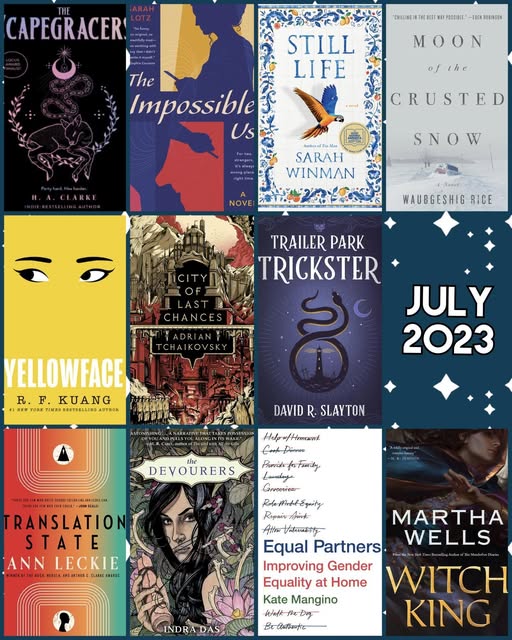

book collage, July 2023

July was a relatively light reading month because family visited and we went on vacation! (Funny enough, I get less reading done on vacation than when I’m at home. Mark of a good vacation.)

The Scapegracers, by H.A. Clarke: The narrator of the Scapegracers, a teenage lesbian witch named Sideways Pike, has never been cool; however, when a trinity of confident, popular girls hires her to perform a showy spell for their Halloween party, she finds in them both a coven for her magic and an unexpected gift of friendship. The other girls are the opposite of insecure: they are brimming with righteousness and rage, ready to rain down curses on anyone who mistreats them or makes them feel lesser (mostly self-centered teenage boys). There are some threats from scary witchfinders and some weird gatekeeping from the occult establishment going on in the background, but mostly this book is a ferocious celebration of loyalty and magic. I love the defiant rejection of the “mean girls clique” trope, and also the diverse cast. First in a series.

The Impossible Us, by Sarah Lotz: Epistolary alternate-universe romp. After struggling author Nick and sassy dressmaker Bee make accidental contact through a misdirected email, they continue to correspond, finding in each other kindred spirits. They eventually make plans to meet… which is when they figure out that they actually live in different universes. Their respective actions after this discovery really do take this book into a new level. Even though things get super weird, the chemistry between Nick and Bee, and their snappy email conversations, keep the book going. Enjoyable plot and shenanigans, though if you start thinking too hard about the ramifications there are some iffy consent issues.

Still Life, by Sarah Winman: A slow, patient journey following Ulysses Temper through four decades (with occasional interludes with Evelyn Skinner, art historian). In 1944 Florence, British soldier Ulysses makes unexpected connections with the people that follow him back to his home in London, and eventually draw him back to Italy. Though Ulysses is the main character, the excellent ensemble cast around him, and their connections to one another, provide the warm heart that centers the story. I love how each of them is allowed space to grow, learn, and change, and how they each do their best to support one another. The writing is just gorgeous and both London and Florence are beautifully and wistfully rendered.

Moon of the Crusted Snow, by Waubgeshig Rice: Post-apocalyptic (though you don’t know it at the beginning) thriller, documenting the experience of a small Anishinaabe community in a reservation in northern Ontario. As the community is already pretty isolated, even more so as winter approaches, their awareness that civilization is collapsing comes slowly; first the power is cut off, then their fuel shipment never arrives. As the tribe attempts to maintain order and community safety, intruders escaping the crumbling south arrive and throw things into disarray. The narrator, a quiet, solid hunter named Evan Whitesky, quietly maintains family and community ties even as he begins to suspect the new arrivals of more sinister intentions. Well-paced, smoothly written.

Yellowface, by R.F. Kuang: When star author Athena Liu dies suddenly, June Hayward pockets her latest manuscript, about Chinese laborers, and then rewrites it and releases it under the name “Juniper Song” (her first and middle names). When the book becomes a smash success, June is accused of misleading people into thinking she might have Chinese ancestry, and finds herself haunted by Athena’s ghost wherever she turns. The book raises questions about racism in the publishing industry, diversity as performance, and ownership in art, but immerses it all in June’s inescapable trainwreck of an unreliable first-person narrative. There is barely a single likeable character in this book but it moves along incredibly well.

City of Last Chances, by Adrian Tchaikovsky: Ilmar is a city at the edge of the Palleseen empire, and one conquered in name but perhaps not in spirit; it is full of restless natives, bitter refugees, starry-eyed students, and ruthless criminals, and also sits on the edge of a haunted magical forest, last resort for the desperate. Tchaikovsky assembles a cast of archetypes and then proceeds to make them into whole characters that grate on one another’s edges and force one another into growth, and sets it against a background of cultural repression and inevitable rebellion. Fascinating read.

Trailer Park Trickster, by David R. Slayton: Book #2 featuring Adam Binder, the queer warlock from a trailer park who just can’t stop saving people (even those who might not deserve saving). This one has him returning to his roots and investigating the increasingly creepy foundations of his family life; meanwhile, his love interest Vicente finds himself navigating dangerous elven politics. I liked the book in general but didn’t like the ongoing trope of “lovers are too busy with mortal peril to discuss their relationship, therefore the angst will continue” which looks like it’ll continue into the third book. Sit down and talk to one another, gentlemen, it’s healthier in the long run.

Translation State, by Ann Leckie: Set in Leckie’s Radch universe, this starts out as a missing-persons mystery and ends with an impassioned argument over one’s right to determine one’s own destiny. I love how Leckie uses truly inventive alien biologies and philosophies to investigate very human questions of identity, self-determination, and found family. Slow start, tense finish, great read.

The Devourers, by Indra Das: South Asian speculative fiction, though it also touches on Nordic and other shapeshifter myths. Narrator Alok Mukherjee is a history professor who meets a mysterious figure who claims to be a half-werewolf; fascinated, Alok agrees to record the stranger’s stories, some oral and some written on human skin. As the stranger’s tale unfolds and Alok is drawn further into the fantastically violent and turbulent history, the relationship between the two of them deepens as well. I liked how the story wove together the mythologies of different cultures, and I also enjoyed how Das took time to develop Alok’s character instead of having him be a passive listener to a story far more interesting than his own life.

Equal Partners, by Kate Mangino: Full disclosure: I’ve met Kate Mangino, and found her book to be every bit as thoughtful, forthright, and considerate as she is. The subtitle for this book is “Improving Gender Equality at Home,” and addresses the imbalance in household gender roles created by harmful social norms. The book doesn’t just lay out examples and statistics, but gently points out familiar social behaviors that can actually perpetuate the problem. Each chapter also offers guided discussion topics and thought exercises to help readers become aware of their own stances and provide avenues for improvement, if it is desired. The book is carefully written to address as wide a spectrum of the modern family as possible, regardless of gender, sexual orientation, generation, and family structure. Even though I consider myself fairly educated and aware of these issues, I still found myself taking many notes on how to be a more equal parent and a more equality-focused person in conversation. Gender norms are deep-seated and addressing them is difficult, but this book provides an informative and understanding base from which to make a start.

Witch King, by Martha Wells: The best thing about Martha Wells’ narrators is that their general exasperation with everything makes them immediately relatable, no matter how weird their selves and circumstances… which is good, because the reader is otherwise thrown straight into a fantasy culture and magic system with absolutely no explanations. This book’s viewpoint character, Kai, is a demon who possesses the bodies of dying humans, and whose closest friends are powerful witches and warriors — useful because they seem to have some very terrifying enemies as well. Through adventure and flashback, Wells builds a portrait of how Kai and his friends were brought together, and how they became instrumental in the formation of the empire’s current political balance. Most of the plot threads are tied together neatly at the end, but it also feels like Wells might be doing some worldbuilding in preparation for future adventures.

A Molecule Away from Madness: Tales of the Hijacked Brain, by Sara Manning Peskin

Through a selection of case studies written like medical mysteries, neurologist Peskin illustrates the terrifying effects of the tiniest changes: from the gene-directed protein synthesis that results in Huntington’s chorea, to a woman whose own immune system flooded her brain with hallucinogens, to a patient whose grip on reality was threatened by what turned out to be a simple vitamin deficiency, this book left me amazed both at the delicate balance our bodies must tread to maintain our brains.