Sequel to Shards of Earth, though a little less focused and more fragmented in the plot. Here Tchaikovsky, having created a huge host of alien cultures and many worlds, seems to want to dig into them and explore them even as his interdimensional space monsters are tearing everything down around them. His characters are pulled in different directions, running from enemies, chasing various leads, and following shadowy cabals, while the interstellar factions stumble (or are perhaps directed) towards war. The whole thing ends on a cliffhanger promising even more action; there is so much going on that I may have to re-read both books before the third is published next year.

Month: October 2022

A Natural History of Dragons: A Memoir of Lady Trent, by Marie Brennan

This memoir begins with Lady Trent acknowledging her own status as a famous dragon naturalist, but reminding the reader that she was once a girl, the daughter of a wealthy landowner, and as such was expected to forgo unseemly activities like reading science texts and studying natural history, and especially was dissuaded from studying dragons. Because it’s a memoir, you know that Isabella eventually achieves her dream of a life of adventure and scientific study, but in this volume you get to relive her early history of rebellion, her attempts at courtship, and her journeys of discovery. I loved Isabella’s narrative voice and the occasional interjections from the future Lady Trent, putting the tale in perspective.

Babel, by R.F. Kuang

This book is subtitled “or the Necessity of Violence: an Arcane History of the Oxford Translators’ Revolution,” which clues the reader into the fact that there will be linguistics nerdity, class struggle, and obviously magic. When words are translated between languages, nuance is sometimes lost; in Kuang’s alternate history, this elided nuance becomes actual magic. What follows explores the British Empire’s domination and exploitation of other nations through the lens of language: how those in power try to make it just another tool of oppression, and how native speakers of those languages are forced into choosing between buying into the system and benefiting from the oppression, or rebelling against it, and losing everything. Robin, the narrator, is taken from China to England at a young age, so that the British magicians can train him to use his language to serve the empire. His gradual awakening to how he is being used, and how he can use what was given him to fight back, makes for a gripping and urgent read. This book made me want to flip madly through to follow the action, and at the same time want to linger over each page, savoring the insights and turns of phrase. A fantastic and beautiful read.

The Island of Missing Trees, by Elif Shafak

The narration in this book switches constantly, from person to person to fig tree; that last narrator almost made me put down the book, because it felt so contrived and twee. But if you can get over being given occasional ecology lectures from a tree, the story underneath is about immigration and loss, and how people adapt when being transplanted (both literally and figuratively) into a foreign land. In this case it’s about people immigrating to England from Cyprus (or choosing to stay) during the 1960s crisis, and how they deal with the pain that they bring with them.

Blackfish City, by Sam J. Miller

This is a post-apocalyptic (or more accurately, during-apocalyptic) cyberpunk novel, which focuses so much on humanity that as a reader, I almost stopped seeing the cyberpunk altogether. It’s almost the opposite of William Gibson type novels, in which the humans are cyphers and the tech is cool; Miller’s humans’ emotions are deep and raw, and the fact that they live in a futuristic city run by mysterious AIs is just another part of their daily lives (though it’s also a huge part of the story). The geothermal city of Qaanaaq, an arctic refuge for those escaping the wars and chaos of a warming world, is visited by a mysterious woman who may or may not be bonded to an orca through exotic and secret technology; meanwhile, ordinary citizens are afflicted by a disease called “the breaks,” which bombard them with glimpses of strangers’ lives. Miller weaves these disparate threads together in a fast-moving and urgent story that also becomes a commentary on how those in political or economic power can dehumanize others, and the importance of family and community in a world being torn apart by climate change.

Seasonal Fears, by Seanan McGuire

Sequel to Middlegame, in that some of the same characters reoccur. This one deals with the embodiment of the seasons, in this case a pair of high school sweethearts too trope-y to be believed: a golden boy football star and his girlfriend the cheerleader. This is Seanan McGuire, though, so the characters are there both as symbols and as people: the football star is an embodiment of Summer, and his girlfriend becomes Winter; they find themselves catapulted into an all-or-nothing struggle to wear the seasonal crowns. McGuire does her best to keep the characters interesting, and her writing is gorgeous as usual… but really this is just a story about people who thought their lives were going to be normal, and who find out that they are actually myths: after a while, it’s hard to see them as entirely human, and therefore hard to care deeply about their journeys.

The Harbors of the Sun, by Martha Wells

#5 in the Books of the Raksura. I really think the books in the series suffer when they leave the personal and go global. Even though the conflict has reached the point where entire species are being threatened, the urgency isn’t there; the writing is still more interesting when addressing with the relationships between the characters (especially how the Raksura deal with the individual Fell, whose gradual gaining of consciousness makes their conflict seem even more tragic). It’s still adventurous, wildly inventive, and fun reading, because Martha Wells is good at what she does… but the first three books were definitely better than the final two.

The Return of the Thief, by Megan Whalen Turner

The conclusion of the Queen’s Thief series was perfect. Once again, the story begins with a narrator seemingly unrelated to any goings-on; once again, the narration and the plot twist around until you can’t possibly conceive of the story taking place any other way. The relationship between the kings and queens of the three countries at the heart of the series is amazingly crafted; they say so few words to one another, but every interaction and glance exchanged shows how close they have become. Such an emotionally satisfying end to the series, and the short story afterwards is a beautiful little finish.

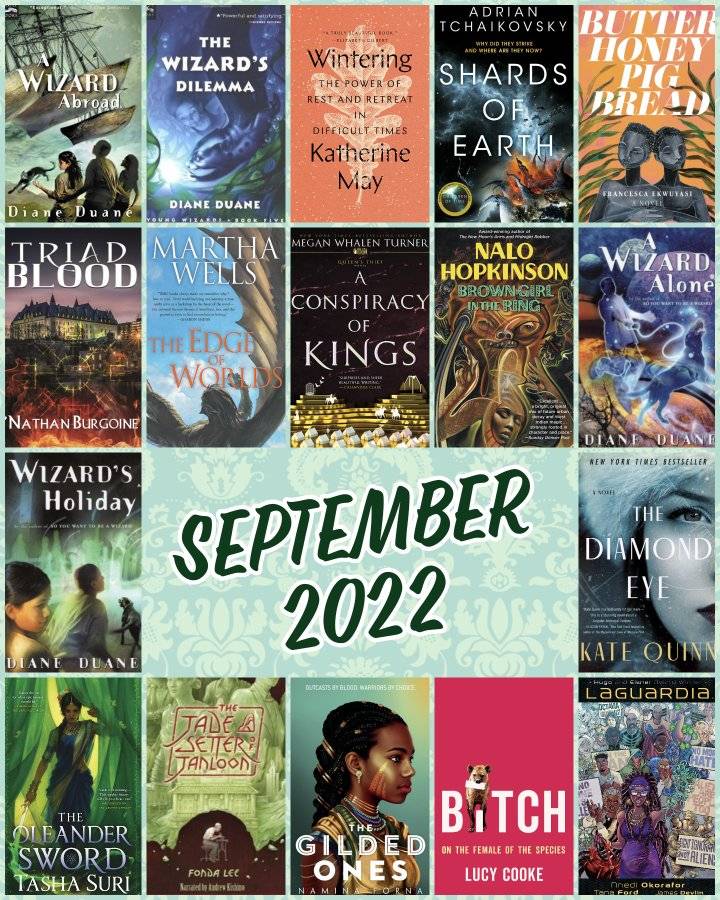

book collage, September 2022

A Wizard Abroad and The Wizard’s Dilemma, by Diane Duane

Wintering: the Power of Rest and Retreat in Difficult Times, by Katherine May

Shards of Earth, by Adrian Tchaikovsky

Butter Honey Pig Bread, by Francesca Ekwuyasi

Triad Blood, by ‘Nathan Burgoine

The Edge of Worlds, by Martha Wells

A Conspiracy of Kings, by Megan Whalen Turner

Brown Girl in the Ring, by Nalo Hopkinson

A Wizard Alone; Wizard’s Holiday by Diane Duane

The Diamond Eye, by Kate Quinn

The Jade Setter of Janloon, by Fonda Lee, narrated by Andrew Kishino

The Oleander Sword, by Tasha Suri

The Gilded Ones, by Namina Forna

Bitch: On the Female of the Species, by Lucy Cooke

LaGuardia, by Nnedi Okorafor, illustrated by Tana Ford